BRICS in the wall of global greed

When we think about the make-up of the global system, we tend to think in terms of nation-states like the USA, Britain, France and Germany and of international institutions such as NATO and the EU.

Indeed, for many years the might of the American state has been the main physical means by which the money-power has imposed its control across the world, it having taken over the role once played by Britain.

For this reason, many fellow anti-imperialists are rejoicing at what appears to be the collapse of this Western empire and its imminent replacement by a “multi-polar world order” based on the BRICS countries – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

However, they would do well to bear in mind that a world order is still a world order, whether or not it terms itself “multi-polar”.

The poles in question are merely geographically diverse manifestations of the same overall network and any “shift” in power towards BRICS can only be regarded as a manoeuvre, an internal reorganisation within the public-private global governance.

This labyrinthine entity, most visible today in the form of its Vanguard-BlackRock financial network, has emerged from the Rothschild dynasty’s long-assembled financial, industrial and institutional empire.

I will here provide historical background showing how each BRICS country has long been under the influence of this worldwide power nexus and then give a brief snapshot of their current participation in the Fourth Industrial Revolution and Great Reset agenda promoted by the same interests.

There is inevitably some overlap with previous writing, particularly my booklet on the Rothschilds, Enemies of the People, but I also present plenty of fresh and relevant material and so I hope readers will bear with me…

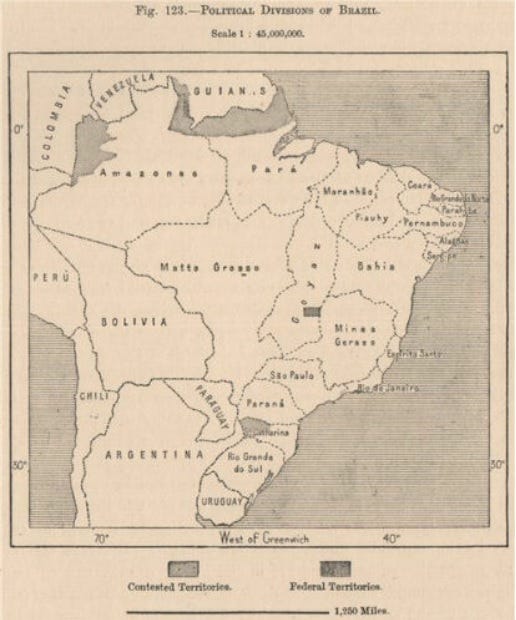

BRAZIL

THE BACKGROUND

Brazil, of course, has never been part of the formal British Empire or Commonwealth, that foundation of today’s global Great Racket. [1]

But in his book on the Rothschilds, Niall Ferguson explains that the London-based financiers enjoyed a “traditionally close relationship” with the massive Latin American country. [2]

Brazil was heavily targeted for exploitation by the Rothschilds from the 1820s onwards, [3] with the coffee trade forming an important aspect of their involvement.

Historian Carroll Quigley writes about the process of commercialization and incipient industrialization of Latin American society which “was largely a consequence of foreign investments, which introduced railroads, tram lines, faster communications, large-scale mining, some processing of raw materials, the introduction of electricity, waterworks, telephones, and other public utilities and the beginnings of efforts to produce supplies for these new activities”. [4]

Notes Ferguson: “The long history of Rothschild involvement in Brazil shows that they did not regard formal imperial control as a precondition of profitable capital export”. [5]

He reports that the Rothschilds loaned £1 million to Brazil to fund its war with Argentina and Uruguay in 1851 [6] and afterwards came the “need” to finance the rapid growth of the country’s railway network, which sparked a £1.8 million loan from the same source.

“It was just the beginning of an exceptionally monogamous financial relationship between the Brazilian government and the London house which, between 1852 and 1914, generated bond issues worth no less than £142 million”, [7] adds the historian.

A lull in Brazilian government borrowing in the 1870s, with the only major issue a £5.3 million loan in 1875, was followed by a fresh bout of activity in the 1880s in which “once again the Rothschilds acted as the government’s sole issuing agent in London”. [8]

Altogether, says Ferguson, the Rothschilds were responsible for Brazilian government bond issues totalling £37 million between 1883 and 1889, as well as £320,000 for the Bahia-San Francisco railway company. [9]

Between 1890 and 1914, the London bankers issued a “staggering” £83 million of Brazilian public sector bonds and a further £5.8 million of private sector securities. [10]

He comments: “Plainly, the Rothschilds had substantial financial leverage over Brazil”. [11]

Indeed, during the First World War, the US ambassador in Brazil commented that “the Rothschilds have so mortgaged Brazil’s financial future that… they will place every obstacle in the way of her entering into banking relations with any other house than their own”. [12]

When the Brazilian government approached the London Rothschilds in 1923 for a £25 million loan “to liquidate the floating debt and set Brazilian finances in order”, the bankers proposed a mission to Brazil in the hope of imposing “some palatable form of foreign financial control”, [13] as they themselves put it.

Despite a spat between Brazil and Britain, the Rothschilds “continued to exercise control over the coffee support scheme”, writes Ferguson, and resumed their “dominant role” on Brazilian federal bond issues when Brazil returned to the gold standard in 1927. [14]

The Rothschild agent in Brazil, Henry Lynch (known locally as ‘Sir Lynch’ after his knighthood), “remained a key figure in the country’s finances throughout the period”. [15]

Brazil’s debts were at times so crippling that governments were forced to suspend repayments on several occasions and Ferguson records that in the 1930s a complete restructuring of the Brazilian debt was arranged with the Rothschilds and other foreign lenders.

“By issuing new bonds, the government was able to pay around £6-8 million annually between 1932 and 1937, though it was not until 1962 that all the sterling bonds were finally liquidated”. [16]

Ferguson reports that in 1965 the Rothschilds helped raise £3m for the Inter-American Development Bank and in 1968 the bank “organised two major loans totalling £41 million to its old client Brazil”. [17]

THE PRESENT

Today, Brazil is considered an “advanced emerging economy”, with a GDP that is the highest in Latin America and in the top ten worldwide. It was recently rated the 9th largest military power on the planet. [18]

Current president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was given the World Economic Forum’s first-ever Global Statesman award in 2010 [19] and this “left-winger” is so keen on Klaus Schwab’s corporate pressure group that he even attended its conference on Africa in a period when he was out of office. [20]

The WEF has now opened a “Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution” in Brazil, which it says aims to “encourage the adoption of new technologies and to improve Brazil’s global value chains, increasing the productivity and competitiveness of Brazilian companies”. [21]

This is described as “a public-private partnership between the Federal Government of Brazil, the Government of the State of São Paulo, and many private sector founding partners”.

In 2019 the Brazilian state launched a programme to “establish indicators and goals and implement solutions to turn Brazilian cities into smart cities”. [22]

Delights in store there include CCTV cameras, face recognition, “farming surveillance” and electronic health records.

Impact investing is well underway in Brazil, “with new investors emerging in the country and the volume of capital available for impact investing increasing”, says one report. [23]

And Brazil’s central bank plans to launch its digital currency in 2024. [24]

Incidentally, the Brazilian flag features the motto “ordem e progresso”, Portuguese for “order and progress”. This is strangely close to “work, order and progress”, the new motto adapted by the Macron regime in France, which at least one commentator considers “thoroughly Rothschildian in tone”. [25]

RUSSIA

THE BACKGROUND

Russia, past and present, has a reputation for being outside the financial power structures that dominate the West. But the historical facts suggest otherwise.

Professor Jean Bouvier, who was a specialist in banking affairs at the Sorbonne in Paris, says Russia played a key role in the Rothschilds’ multi-polar “financial pre-eminence”, which he dates back to 1818. [26]

Ferguson depicts the Rothschilds at this time as being key backers of The Holy Alliance, authoritarian monarchies defending the old aristocratic order.

“They enabled Austria, Prussia and Russia – the members of the Holy Alliance – as well as the restored Bourbons in France, to issue bonds at rates of interest only Britain and Holland had previously been able to enjoy”. [27]

The Rothschilds played a role in Russia’s “financial preparations” for the European war over Italian independence in 1859. [28]

They were also heavily involved in a series of loans for railway-building in Russia, particularly in the 1870s and 1890s. [29]

Widespread control of the railway infrastructure tied in nicely with heavy involvement in the oil industry.

Historians Gerry Docherty and Jim Macgregor write: “The Rothschilds, behind a myriad of different company titles, constructed oil tank wagons for the railways, storage depots and refineries for the production of petrol and kerosene, and bartered with Government departments over concessions and favorable rail cargo fares”. [30]

They were notably involved in the Russian oilfields around Baku, now in Azerbaijan, where they “amassed vast and highly profitable investments”. [31]

“Immobilising vast capital” in a refinery at Novorossiysk and an oil depository in Odessa, the French Rothschilds’ investments in Russian oil by the end of the 19th century were worth some 58 million francs. [32]

Says Ferguson: “At peak, around a third of Russian oil output was Rothschild-controlled”. [33]

The Rothschilds also went into partnership with Pollack & Co, a Russian shipping firm, and the International Bank of St Petersburg to form a new company, Mazout, so as to expand their sales to the Russian domestic market. [34]

Relations between the Rothschilds and Russia were not always easy. Their French branch tried and failed to “establish a new Rothschild foothold” in St Petersburg on a number of occasions. [35]

But between 1870 and 1875, the London and Paris Rothschilds jointly issued Russian bonds worth a total of £62 million, “thus finally securing that influence over Russian finances which had eluded them for so long”. [36]

This was also, says Ferguson, “profitable business” for the Rothschilds, with the price of the bonds leaping up by 24% between 1870 and 1875. [37]

In 1889 the Paris Rothschilds undertook two major Russian bond issues with a total face value of some £77 million, with the London Rothschilds joining in these operations by taking a share in a third £12 million issue in 1890. [38]

There was controversy in Russia over the terms of the 1889 Rothschild loan to the Russian Treasury, which was more costly than a previous “non-Rothschild loan”. [39]

Having reasserted their financial links to Russia, “the Rothschilds now sought to exert pressure on the Russian government”, publicly criticising its treatment of Jews. [40]

But, says Ferguson, “the Rothschilds had strictly financial reasons for blowing hot and cold towards Russia”. [41]

He cites in this context short-term deposits of Russian gold with the London Rothschilds and disagreements about Russian trade policy – “specifically its protective tariffs on imports of rails and its new tax on oil exports”. [42]

This policy was bound to be an issue, given the Rothschilds’ serious involvement in both railways and oil in Russia.

The Rothschilds appear to have been finally persuaded to resume financial operations with Russia by the appointment of a new finance minister, Count Witte, whose wife was reported by German diplomat Count Münster to be “an intelligent and very intriguing Jewess” who was “of great help in bringing about an understanding with the Jewish bankers”. [43]

Comments Ferguson: “The fact that the Rothschilds privately alluded to the Jewish origins of Witte’s wife lends credibility to this interpretation”. [44]

He adds that the Rothschilds may also have been “attracted by Witte’s stated objective of putting Russia on to the gold standard, which accorded with their global interests in gold mining and refining”! [45]

A 400-million-franc Rothschild-led loan to the Russian government in 1894 was followed by another for the same sum in 1896, for which Alphonse de Rothschild was decorated with the Grand Cross by the czar. [46]

Finance was an increasingly important factor behind geopolitical “diplomacy” and war at this time.

Ferguson writes: “Of all the great powers, Russia relied most heavily on foreign lending in the period before 1914; and the predominance of France as Russia’s main source of external finance had as its corollary a diplomatic rapprochement between the two powers…

“This Franco-Russian entente was one of the defining diplomatic developments of the 1890s; and the Rothschilds played a central role in it – despite their strong antipathy towards the Tsarist regime’s anti-Jewish policies”.

In 1901 Russia took out yet another loan from a Rothschild-led consortium, this time for 425 million francs. [48]

After secretly financing the Japanese in their successful war against Russia in 1904-1906, and then openly lending £48 million to help build back the post-war Japanese economy, [49] the Rothschilds also profited from the war on the Russian side.

“Russian industry recovered spectacularly thanks to the Rothschilds and other international bankers who poured massive loans into the country”, [50] Docherty and Macgregor note.

The official Rothschild attitude to the 1917 Russian Revolution and the new Bolshevik regime was negative – “As late as 1924, in the period of the New Economic Policy, Rothschild views of Soviet Russia remained so hostile as to preclude even the acceptance of a deposit from one of the new Soviet state banks”, says Ferguson. [51]

However, the “socialist” victory was not what it seemed. As eye-witnesses like the Russian anarchist Voline were at pains to point out, the event in fact amounted to a counter-revolution against the threat of an authentic people’s revolt.

The secretive involvement in the Bolshevik coup of Rothschild associates, including that great British believer in the “highly-organised state”, Alfred Milner, [52] is well documented in Professor Antony C. Sutton’s brilliantly-researched book Wall Street and the Bolshevik Revolution. [53]

Another important player was banker William Boyd Thompson, who in 1914 had become the first full-term director of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Thompson, explains Sutton, “became an ardent supporter of the Bolsheviks, bequeathing a surviving symbol of this support – a laudatory pamphlet in Russian, ‘Pravda o Rossii i Bol’shevikakh’”. [54]

Docherty and Macgregor explain that Thompson was “a loyal Morgan man” and stress that J.P. Morgan and the entire Morgan Empire were “very firmly connected to Rothschild influence”. [55]

They add: “Writing in 1974, Professor Sutton was clearly unaware that virtually the entire international banking cabal was linked through a complex chain that led back to the Rothschilds in London and Paris”. [56]

In addition to its role in suppressing real people power, the Soviet New Normal benefited Rothschild interests by pushing massive industrialisation, including electrification dependent on their copper supplies, and by forcing peasants off the land and into factories in a manner typical of each of the industrial so-called “revolutions”.

Quigley comments that Marxist theory was generally welcomed by the rich and powerful in Russia because it “postponed revolution until after industrialization had proceeded far enough to create a fully developed bourgeois class and a fully developed proletariat”. [57]

THE PRESENT

Russia, the largest country in the world, today has the ninth highest population. [58]

Foreign investment and high oil prices saw the Russian economy boom at the start of the 21st century.

President Vladimir Putin has a long history of involvement with the World Economic Forum, [59] dating back [60] to 1992, [61] though he has not been invited to Davos since the Ukraine conflict began.

In 2021, the WEF announced the opening of a Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution in Russia, for which “artificial Intelligence and IoT are key areas of focus”. [62]

The market for “solutions for smart cities” in Russia exceeded 81 billion rubles at the end of 2019, says one report. [63]

Another article adds: “Moscow sees the UN’s Agenda 2030 as an excellent opportunity to enhance the livability of Russia’s capital and transform it into a smart city”. [64]

This is being boosted by “Investment Strategy 2025”, which is “a series of reforms that aim to attract foreign investors by creating a favourable investment climate by cutting bureaucracy”.

Russia already boasts its own “impact investing industry” [65] and is to start piloting a “digital rouble” in August 2023. [66]

As Moscow-based journalist Riley Waggaman puts it on his Edward Slavsquat blog: “Yes, Russia is complicit in the Great Reset”. [67]

INDIA

THE BACKGROUND

India was, of course, an important part of the British Empire and so, until 1950, various private financial interests enjoyed access to its vast wealth via the “law and order” imposed on their behalf by the British state.

Quigley adds: “Britain was obsessed with the need to defend India, which was a manpower pool and military staging area vital to the defense of the whole empire”. [68]

“British rule in the period 1858-1947 tied India together by railroads, roads, and telegraph lines.

“It brought the country into contact with the Western world, and especially with world markets, by establishing a uniform system of money, steamboat connections with Europe by the Suez Canal, cable connections throughout the world, and the use of English as the language of government and administration”. [69]

India’s subsequent inclusion in the Commonwealth was, as Quigley points out, a long-planned ploy to keep it firmly within the British sphere of control despite its apparent “independence”.

He quotes a letter from British imperialist Lionel Curtis in 1916 which states: “We must do our best to make Indian Nationalists realize the truth that like South Africa all their hopes and aspirations are dependent on the maintenance of the British Commonwealth and their permanent membership therein”. [70]

British imperialists perfected state-corporate rule, otherwise known as public-private partnerships or stakeholder capitalism, centuries before it was adopted by Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler.

By the start of the 1600s it was clear to the merchants of London that “there were big profits to be made in overseas trade”, writes historian Christopher Hill. [71]

The East India Company, formed in 1601, was making a profit of 500% by 1607 and basically administered India in a public-private arrangement with the British state until 1858.

Hill notes that the company, like The Royal African Company, “enjoyed the peculiar patronage of the government” and that both were “deeply involved in politics”. [72]

In A People’s History of England, A.L. Morton describes the firm as “the real founder of British rule in India”, [73] being “the first important joint stock company” which allowed it “a continuous development”, [74] which would today no doubt be termed “sustainable development”.

The East India Company was also notoriously corrupt and violent, to the point that in the 18th century even the company’s own directors were forced to condemn the fact that “vast fortunes”

had been obtained by “the most tyrannic and oppressive conduct that was ever known in any country”. [75]

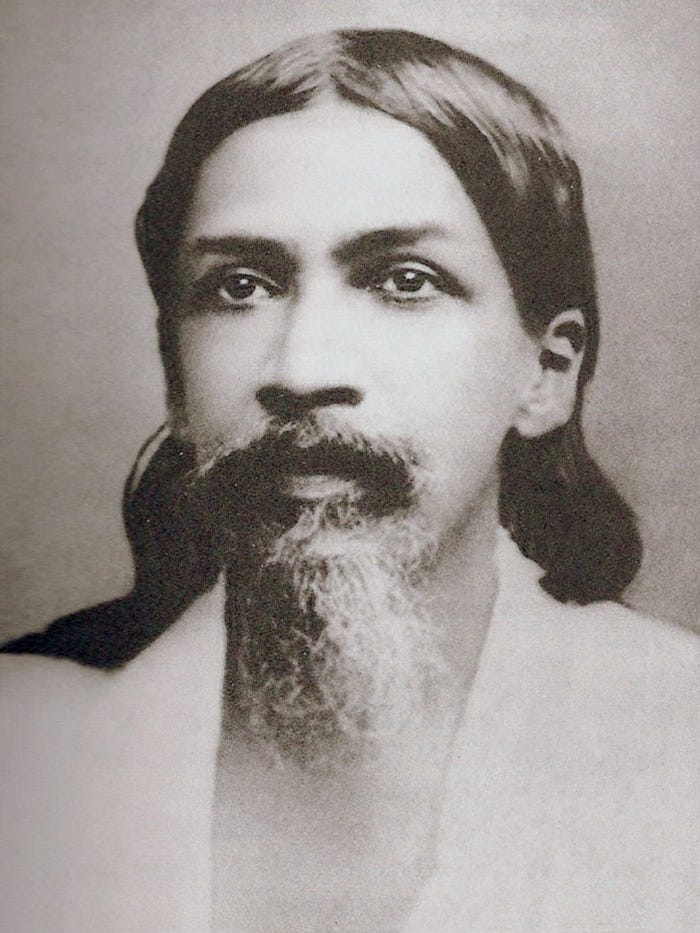

Indian freedom fighter and metaphysician Sri Aurobindo (1872-1950), pictured here, writes of “a radical and congenital evil implied in the very existence of British control”. [76]

He adds: “The huge price India has to pay England for the inestimable privilege of being ruled by Englishmen is a small thing compared with the murderous drain by which we purchase the more exquisite privilege of being exploited by British capital”.

Ferguson says that the Rothschilds, “in a league of their own as an authentically global operation”, made important “advances” in India in the mid 19th century.

There was no telegraph link from Europe until 1866 and “the Rothschilds’ traditional system of semi-autonomous agents, corresponding regularly but not in daily contact, remained unsurpassed”. [77]

Part of the interest for the Rothschilds lay in India’s opium, used for trading with China and also brought back to Europe, and by the late 1850s they were in regular correspondence with a Calcutta firm, Schoene Kilburn & Co. [78]

This involvement meant that anti-imperial uprisings like the Indian Mutiny of 1857 “had a resonance in New Court [the Rothschilds’ London HQ] which previous Asian upheavals had lacked”, [79] explains Ferguson.

“For the first time, the bank was becoming involved in the commerce of the British Empire, a field it had previously left to others”.

This involvement attracted some controversy in 1875 when prime minister Benjamin Disraeli turned to his friends the Rothschilds to finance Britain’s purchase of nearly £4 million of shares in the Suez Canal, [80] a crucial aid for British trade with India, shortening the sea route to Bombay (Mumbai) by more than 40 per cent. [81]

The outraged former Chancellor of the Exchequer Sir Robert Lowe pointed out that the Rothschilds’ total charges of £150,000 for a three-month loan amounted to 15 per cent per annum interest! [82]

Ferguson says that despite their business dealings in India, and the naming of a tea plantation after them by relatives Gabriel and Maurice Worms, the Rothschilds were not greatly interested in the sub-continent for much of the 19th century.

“After 1880, however, that changed. Between 1881 and 1887, Charlotte’s [Rothschild] sons were responsible for issuing Indian railway shares worth a total of £6.4 million”. [83]

Part of this “blossoming of the Rothschilds’ interest in India” [84] was thanks to prime minister Lord Salisbury, whom the Rothschilds had “fervently” wished to remain in power at the end of 1885. [85].

Salisbury appointed, as Secretary of State for India, a politician by the name of Randolph Churchill (pictured), father of Winston, who died owing an enormous £66,902 to the Rothschilds. [86]

While planning the issue of a loan for the Indian Midland Railway, Churchill specifically told the Viceroy, Lord Duffering: “When the loan is brought out I shall fight a great battle against [Bertram] Currie to place it in the hands of the Rothschilds”. [87]

Ferguson adds: “Churchill’s biographer Roy Foster suggests that the Rothschilds did indeed help to place the new company’s shares. Contemporaries also assumed that Churchill’s decision to annex Burma – announced on New Year’s Day 1886 – was linked to his growing intimacy with the Rothschilds”. [88]

THE PRESENT

India’s population is now the biggest of any country in the world, having just overtaken China’s 1.425 billion. [89]

This is a huge market for global profiteers: the International Monetary Fund judged the Indian economy in 2022 to be nominally worth $3.46 trillion. [90]

Prime minister Narendra Modi has been a regular attendee at the World Economic Forum’s Davos events, where he has “pitched for India as an investment destination” emphasising efforts to “improve the ease of doing business”. [91]

He says: “The ability of Indians to adapt to new technologies, their spirit of entrepreneurship, can give all our global partners renewed energy”. [92]

Ah, those all-important “global partners”!

Modi says that India has the ability to lead the Fourth Industrial Revolution, citing “decisive governance” as a key factor – Mussolini and Hitler are no doubt applauding from the pits of hell.

India’s “heavy industries minister” Mahendra Nath Pandey declared: “India is moving towards becoming a hub of global manufacturing… 3D printing, machine learning, data analytics and IoT are key to promoting industrial growth”. [93]

India, too, has its own Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution, in Mumbai, announced by the WEF in January 2018. [94]

It also boasts an official Smart Cities Mission, [95] whose “partners” include the British, French and American governments, US Aid, The Rockefeller Foundation and the World Bank. [96]

I have already reported how the digital slavery that is impact investment is being promoted in India both by King Charles III’s British Asian Trust, cheered on by venture capitalist Sir Ronald Cohen, [97] and by Ashoka, a strange organisation funded by “charitable foundations”. [98]

But it seems the global impact vultures are now getting even more excited about the profits they can extract from the Indian people.

“India is one of the most fertile environments for impact investors to seek opportunities”, declares a report on the WEF’s website. [99]

The authors enthuse: “Digital penetration in India has allowed tech-enabled businesses to scale impact and drive innovation across sunrise sectors, such as climate-tech and future of work”.

The WEF also shares the wonderful news that “India’s central bank has rolled out a pilot of its proposed digital rupee, enlisting nine private and state-owned banks”. [100]

CHINA

THE BACKGROUND

After millennia of proud independence, the Chinese were dragged into the modern commercial world-system by what they call the “hundred years of humiliation”, which began in 1839 with the first of two “Opium Wars”. [101]

This was nothing short of a disaster. As Quigley writes: “We can see the process by which European culture was able to destroy the traditional native cultures of Asia more clearly in China than almost anywhere else”. [102]

Here he finds the cause of subsequent revolutionary violence: “The impact of Western culture on China did, in fact, make the peasant’s position economically hopeless”. [103]

The agenda behind the Opium Wars, waged by Britain and France, was blatantly a business one, as “Chinese resistance to European penetration was crushed by the armaments of the Western Powers, and all kinds of concessions to these Powers were imposed on China”. [104]

China was forced to open specified treaty ports (including Shanghai) to Western merchants and cede sovereignty over Hong Kong to the British Empire. [105]

The immediate issue at stake was the Chinese bar on the importation of opium from British-controlled India in exchange for Chinese teas and silks, a lucrative if ethically dubious trade in which, as mentioned above, the Rothschilds had a hand.

Ferguson states that the war of 1839-1842 “created attractive new possibilities for British business” and eroded the power of Chinese merchants. [106]

He adds that by 1853 the Rothschilds’ business “was in regular correspondence with a Shanghai-based merchant firm, Cramptons, Hanbury & Co, to whom it made regular shipments of silver from Mexico and Europe”. [107]

Two decades later the dynasty’s obvious power in Chinese affairs was such that when the British magazine The Period published, in 1870, a cartoon depicting Lionel Rothschild as “The Modern Croesus”, a new Rothschild “king” upon his throne of cash and bonds, one of the lesser rulers he was shown lording it over was the Emperor of China. [108]

In the light of today’s talk of a “multi-polar” world order, it is interesting to read Ferguson’s comment that the Rothschilds favoured “co-operation between the European powers” in China and that they generally preferred “what might be called multinational imperialism”. [109]

Natty Rothschild wrote in 1899 of his pleasure at Germany’s “desire to combine with England (and possibly with America and Japan) for commercial purposes in China”. [110]

Ferguson describes in some detail the Rothschilds’ key role in Anglo-German co-operation over China.

“Since 1874, the date of the first foreign loan raised for Imperial China, the Chinese government’s principal source of external finance had been two British firms based in Hong Kong, the Hong Kong & Shanghai Banking Corporation [HSBC] and Jardine, Matheson & Co”. [111]

But German profiteers wanted a piece of the action and banker-imperialist Adolphe Hansemann approached the Rothschilds and HSBC (whose old crest is pictured here) with a proposal to divide Chinese government and railway finance equally between the British and German members of a new syndicate.

“The Rothschilds had no objection to this”, [112] notes Ferguson and indeed their Frankfurt operation was one of the German banks that formed the Deutsche-Asiastische Bank in 1889.

The Rothschilds’ involvement in both prongs of this transnational imperialist partnership is further confirmed by the fact that they financed a fact-finding trip to China by one of the younger members of the German-based Oppenheim banking family. [113]

One of the Rothschilds’ main French operations, Banque Paribas, also got involved, in 1895, participating in a £15 million loan to China, which passed through the intermediary of the Russian state. [114]

There was a strange echo of this manoeuvre in 1954, when the USSR offered “Soviet finance, equipment and specialized skills for an all-out industrialization of China (the so-called ‘great leap forward’)”. [115]

Was Russia again merely an intermediary in this arrangement? What was the ultimate source of the finance for an earlier version of the industry-accelerating Great Reset?

Back in 1895, Natty Rothschild and Hansemann “sought to promote a partnership between the Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank and the new Deutsche-Asiastische Bank”, hoping for “suitable official backing from their respective governments”. [116]

An agreement between the two banks was duly signed in July of that year.

Ferguson writes: “For Natty [Rothschild], the main aim of this alliance was to end competition between the great powers by putting Chinese foreign loans in the hands of a single multinational consortium”. [117]

At a conference of bankers and politicians in London in September 1898 it was agreed to divide China into “spheres of influence” for the purpose of allocating rail concessions; leaving the Yangste Valley to the British banks, Shantung to the Germans and splitting the Tientsin-Chinkiang route. [118]

Ferguson explains that a real pattern of collaboration had been established: “When the Germans sent an expedition to China following the Boxer Rising and the Russian invasion of Manchuria in 1900, they used the Rothschilds to assure London that ‘the Russians won’t risk a war’, and in October Britain and Germany signed a new agreement to maintain the integrity of the Chinese Empire and an ‘Open Door’ trade regime.

“This was without doubt the high water mark of Anglo-German political co-operation in China; but it is important to recognise that business co-operation continued for some years to come”. [119]

Any criticism of this financial-imperialist stitch-up was, of course, unwelcome.

When The Times’ correspondent in Peking/Beijing attacked the cosy arrangement between British and German banks in China in 1905, Natty Rothschild complained to his editor. [120]

As mentioned in passing, the Chinese Revolution, sparked by the effects of a hundred years of destruction and exploitation by imperialist profiteers, only made things worse.

Quigley says Mao’s “Great Leap Forward”, which began in 1958, was “a social rather than simply an agrarian revolution, since its aims included the destruction of the family household and the peasant village.

“All activities of the members, including child rearing, education, entertainment, social life, the militia and all economic and intellectual life came under the control of the commune.

“In some areas the previous villages were destroyed and the peasants were housed in dormitories, with communal kitchens and mess halls, nurseries for the children, and separation of these children under the communes’ control in isolation from their parents at an early age.

“One purpose of this drastic change was to release large numbers of women from domestic activities so that they could labor in fields or factories.

“In the first year of the ‘Great Leap Forward’, 90 million peasant women were relieved of their domestic duties and became available to work for the state”. [121]

The Communist Revolution in China didn’t seem to worry the Rothschilds, who today proudly announce on their website: “Our business was one of the first Western business institutions to re-establish relations after 1953”. [122]

THE PRESENT

China is today the most important BRIC in the wall of global greed.

In 2022, WEF founder Klaus Schwab told Chinese state media that the country was a “role model” for other nations and praised its “tremendous” economic achievements over the last 40 years. [123]

Addressing the WEF’s 14th Annual Meeting of the New Champions in Tianjin, China, in June 2023, Chinese premier Li Qiang said: “China is committed to building world peace, promoting global development and upholding the international order.

“Today, the Chinese economy is deeply integrated into the world economy. China has developed itself by embracing globalization, and grown into a most staunch force for globalization”. [124]

Because China is a “Unitary Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist republic” [125] run by the Chinese Communist Party, some people conclude that the Great Reset agenda pushed by its friend Schwab is a “Communist” one.

But it is never a good idea to accept a label at face value without having a proper look at the content.

The theme of the conference addressed by the Communist Party’s Qiang was “Entrepreneurship: The Driving Force of the Global Economy” and the WEF is a business organisation, which describes itself as “the global platform for public-private cooperation”. [126]

What the financial forces behind the WEF like about Chinese-style Communism, and liked about Soviet Communism, Italian Fascism and German Nazism, is that authoritarian one-party control frees them from the constraints and complications of public accountability.

It allows them to get on with the task of extracting as much profit as possible from people and planet by means of undemocratic “agile governance”, in Schwab’s words, or “decisive governance”, in Modi’s.

When China reinvented itself as a “socialist market economy” in the late 20th century, it first opened up the country to foreign investment and then privatized and contracted out much state-owned industry. [127]

Today China has become known as “the world’s factory” not just because of its famously low labour costs (ie. underpaid workers) and use of child labour, but also because of its “strong business ecosystem, lack of regulatory compliance, low taxes and duties, and competitive currency practices”, says the Investopedia website. [128]

China was being hailed by the WEF for its leading role in the Fourth Industrial Revolution in 2019, [129] even before the Covid starting-gun was fired and, like Brazil, Russia and India, it has its own Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution. [130]

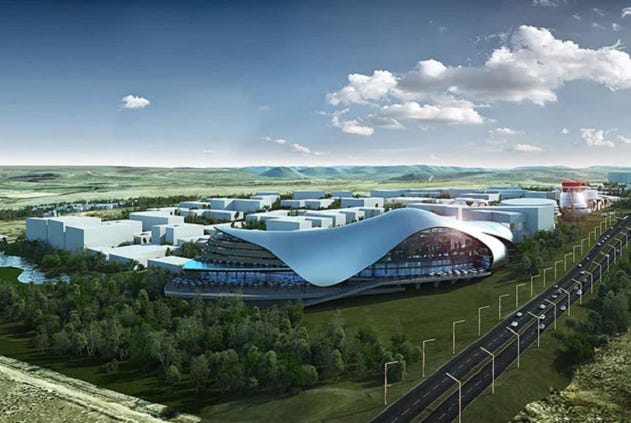

Chinese tech giant Tencent didn’t waste any time in announcing, in June 2020, that the “post-pandemic world” needed smart cities like Net City (plans pictured), “a 2 million square metre (21.5 million square feet) neighbourhood in the southeastern city of Shenzhen”. [131]

“More than 500 smart cities are being built across China, according to government data, equipped with sensors, cameras, and other gadgets that can crunch data on everything from traffic and pollution, to public health and security.

“Net City will use technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and autonomous vehicles”.

In China, the impact investing industry “remains in its initial stage of development” but it seems “advances” have now been made “in areas such as healthcare and financial services”. [132]

China’s controversial social credit system [133] is plainly a model the global ruling class would like to see rolled out everywhere and it also seems to be ahead of the game regarding digital currency – “139 million people have now used China’s digital yuan app, as the country accelerates toward a more digitized economy”, claims the WEF. [134]

SOUTH AFRICA

THE BACKGROUND

The last of the five supposedly “independent” emerging BRICS countries, South Africa, is not only part of the British Empire/Commonwealth but also played an important role in the growth of the Rothschilds’ prosperity and power.

One of their key historical collaborators there was Cecil Rhodes (1853-1902), the British imperialist who gave his name to Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe.

Rhodes had emigrated from England to South Africa as a young man and, while working at the Kimberley diamond fields, he attracted the attention of a Rothschild agent, who was assessing the local prospects for investment in diamonds.

Docherty and Macgregor explain: “Backed by Rothschild funding, Cecil Rhodes bought out many small mining concerns, rapidly gained monopoly control and became intrinsically linked to the powerful House of Rothschild”. [135]

Ferguson remarks that Natty Rothschild “drove a hard bargain” when Rhodes sought his financial backing for his De Beers diamond company to buy the rival Compagnie Française.

“Essentially, Rothschilds advanced £750,000 in cash in return for 50,000 new De Beers shares at £15 each, plus £200,000 in debentures.

“For this, they received a commission of £100,000, but also half the difference between the £15 price paid for the De Beers shares and their London market price on October 5, 1887”. [136]

This apparently implied an additional £150,000 so that the Rothschilds were paid £250,000 for lending £750,000!

The Rothschilds ended up holding more shares in the company than Rhodes himself [137] and had “a substantial financial hold over Rhodes”, stresses Ferguson. [138]

When the new De Beers Consolidated Mines had control of 98 per cent of South Africa’s diamond output, the next step was to establish global domination of the market.

In 1890 De Beers created a cartel with “five friendly firms led by Wernher, Breit & Co”. [139]

Says Ferguson: “As this was the kind of thing the Rothschilds had traditionally done to maintain the price of mercury and were also doing with copper, the syndicate soon received Natty’s blessing”. [140]

Gold had also long been an area of interest for the Rothschilds and via the Exploration Company – an “obvious” Rothschild front according to Ferguson – they were enthused by “the dramatic expansion of South African gold production”. [141]

He adds: “The Rothschilds’ indirect participation in the South African gold boom through the Exploration Company has often been underestimated… Small wonder the English Rothschilds encouraged the spread of the gold standard”. [142]

Rhodes was also involved in exploiting South African gold and again turned to the Rothschilds for political and financial backing.

In particular his firm, Consolidated Gold Fields, wanted to grab previously untapped gold fields north of the Transvaal, ruled by the Matabele King Lobengula.

Rhodes wrote to Natty Rothschild, in 1888, to say: “The Matabele king… is the only block to Central Africa as, once we have his territory, the rest is easy, as the rest is simply a village system with a separate headman, all independent of each other”. [143]

Rhodes and the Rothschilds got their way, thanks to the helpful intervention of the British army in 1893.

King Lobengula’s 8,000 spearmen and 2,000 riflemen [144] were, unsurprisingly, no match for the British troops’ modern machine guns, supplied by Maxim-Nordenfelt, an arms firm in which the Rothschilds had a substantial shareholding. [145]

Arthur de Rothschild described this defeat of the Matabele warriors as “a sharp engagement… 100 of them having been killed, whilst there was, I am happy to say, hardly a single casualty on our side”.

He was pleased to report “a little spurt in the shares” of his family’s business. [146]

The Boer War of 1899-1902 was essentially a grab of gold and diamond resources for Rothschild interests, including De Beers.

Natty Rothschild pretty much confirmed this through the wording of a letter to Rhodes.

He warned his collaborator: “Be careful in what you say regarding the conduct of the war and your relations with the military authorities.

“Feeling in this country is running high at present over everything connected with the war and there is a considerable inclination, on both sides of the House, to lay the blame for what has taken place on the shoulders of capitalists and those interested in South African Mining.

“It would be a great pity to add fuel to the fire and you would only be playing into the hands of the opposition which I am sure you want to avoid.

“I hope, therefore, that you will be careful in your utterances and if you have any complaints to make against the War Office underlings, you will no doubt have opportunities to do so privately”. [147]

It is interesting to note that in 1889 The British South Africa Company, set up by Rhodes, received a Royal Charter modelled on that of the British East India Company.

Right up until the mid 20th century it remained “a very lucrative investment opportunity, yielding very high return to investors”, says Wikipedia. [148]

Financially backed by the Rothschilds, it is a prime example of the public-private partnerships favoured by global imperialists.

THE PRESENT

Contemporary South Africa’s economy is the most industrialized and technologically advanced in Africa and at the same time it has a high rate of poverty and unemployment, being ranked in the top ten countries in the world for income inequality. [149]

Its president, Cyril Ramaphosa, is an eager participant in the WEF’s attempts to “accelerate action on Africa” and he has declared: “This is Africa’s century, and we want to utilize it to good effect”. [150]

He told the Davos event in 2019: “We have entered a new period of hope and renewal, and over the last year have taken decisive steps to correct the mistakes of the recent past and put the country back on the path of progress that we embarked upon in 1994.

“We have placed the task of inclusive growth and job creation at the centre of our national agenda.

“At the inaugural South Africa Investment Conference in October last year, both local and international companies announced around $20 billion of investments in new projects or to expand existing ones.

“Direct foreign investment into South Africa increased by more than 440% between 2017 and 2018, from $1.3 billion to $7.1 billion”. [151]

Ramaphosa added that they aimed to further increase this foreign investment by “our efforts to create an environment that is even more conducive to investment”.

He did not spell out what exactly that might imply for the people of South Africa.

On becoming president, Ramaphosa “put the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) into his national economic strategy”, explains one report.

But it adds: “South Africa has a significant skills shortage, due to failings in its education system, limiting the supply of managers, researchers and workers needed for 4IR. There are also problems of poor quality infrastructure, reflecting weak governance and state capture”. [152]

In 2020 Ramaphosa launched the Mooikloof Mega-City development in Pretoria, one of three smart cities projects in South Africa.

The mega-city is a public-private collaboration with developers Balwin Properties and “may end up becoming the world’s largest sectional property development”. [153]

Another report says smart cities are offering South Africans “a glimpse of a connected future”.

It adds: “With the UN declaring Internet access a human right, many people are realising that online connectivity is just as important as other services like water or electricity.

“Smart cities are the encapsulation of achieving the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as set out by the United Nations”. [154]

In July 2023 Cape Town in South Africa hosted the Africa Impact Summit – “Unleashing African Potential through Impact Investing”. [155]

Impact Investing South Africa [156] says it wants to “learn from and share with the Global Steering Group for Impact Investing”, an organisation funded by the likes of The Ford Foundation, The Rockefeller Foundation, George Soros’ Open Society Foundations, the UK government and the Rothschilds’ BNP Paribas bank. [157]

Its chairman is Ronald Cohen, “the father of British venture capital”, whose activities will by now be familiar to my regular readers. [158]

In May 2021 the South African Reserve Bank embarked on a study [159] to look into the feasibility of a central bank digital currency and in 2023 was said to be “still investigating and testing”. [160]

POSTSCRIPT: THE BANKER BEHIND THE BRICS BRAND

It is surely no coincidence that the man who invented the BRICS acronym, Jim O’Neill, [161] now Lord O’Neill of Gatley, worked for Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, Marine Midland Bank (later HSBC Bank USA) and the Swiss Bank Corporation.

He is a WEF contributor [162] and is connected both to European economic “think tank” Bruegel [163] and to the World Bank. [164]

O’Neill is a former UK Treasury minister [164] and, significantly, was chairman of Chatham House, [165] also known as The Royal Institute of International Affairs, which has long played a central role in advancing the global corporate-neocolonial agenda.

Granted a Royal charter in 1926, it was set up by imperialist schemers such as Milner and Curtis and helped on its way with a gift from J.P. Morgan, which we already know to be yet another Rothschild front. [166]

Quigley warns that when one understands its real origins and purpose, the influence of pseudo-independent Chatham House “appears in its true perspective, not as the influence of an autonomous body but as merely one of many instruments in the arsenal of another power”. [167]

It seems to me that this description applies equally well to the BRICS entity given its name by Chatham House’s former chairman.

And so for what purpose is BRICS an instrument in the arsenal of a certain self-concealing power?

O’Neill himself spelled it out in a 2021 interview with the International Monetary Fund – it is nothing less than the creation of a new form of “global economic governance”. [168]

NOTES

[1] https://winteroakpress.files.wordpress.com/2023/06/the-great-racket-paul-cudenec.pdf

[2] Niall Ferguson, The House of Rothschild: The World’s Greatest Banker 1849-1998 (New York: Penguin, 2000), p. 460.

[3] Ferguson, p. 461.

[4] Carroll Quigley, Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in Our Time (Reprint, New Millennium Edition, New York: Macmillan, 1966), p. 713.

[5] Ferguson, p. 294.

[6] Ferguson, p. 68.

[7] Ferguson, p. 68.

[8] Ferguson, p. 345.

[9] Ferguson, p. 345.

[10] Ferguson, p. 346.

[11] Ferguson, p. 346.

[12] Ferguson, p. 460.

[13] Ferguson, P. 461.

[14] Ferguson, p. 461.

[15] Ferguson, p. 461.

[16] Ferguson, p. 464.

[17] Ferguson, p. 485.

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brazil

[19] https://www.americasquarterly.org/blog/world-economic-forum-honors-lula/

[20]

https://businessday.ng/exclusives/article/lula-obasanjo-kofi-anan-mbeki-and-gordon-brown-to-attend-wef/

[21] https://www.weforum.org/organizations/centre-for-the-fourth-industrial-revolution-brazil

[22] https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/en/geral/noticia/2019-07/brazil-launches-initiative-sustainable-smart-cities

[23] https://andeglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Impact-investment-in-Brazil-2020.pdf

[24] https://www.reuters.com/markets/currencies/brazil-central-bank-launch-its-digital-currency-2024-2022-12-13/

[25] https://winteroak.org.uk/2023/05/15/work-order-progress/

[26] Jean Bouvier, Les Rothschild (Brussels: Editions Complexe, 1983), p. 70.

[27] Ferguson, p. xxiii.

[28] Ferguson, p. 99.

[29] Bouvier, p. 273.

[30] Jim Macgregor and Gerry Docherty, Prolonging the Agony:

How the Anglo-American Establishment Deliberately Extended WWI

by Three-and-a-Half Years (Walterville, OR: Trine Day, 2018), p. 293.

[31] Macgregor and Docherty, Prolonging the Agony, p. 290.

[32] Ferguson, p. 355.

[33] Ferguson, p. 355.

[34] Ferguson, p. 355.

[35] Ferguson, p. 184.

[36] Ferguson, p. 306.

[37] Ferguson, p. 306.

[38] Ferguson, p. 379.

[39] Ferguson, p. 379.

[40] Ferguson, p. 379.

[41] Ferguson, p. 380.

[42] Ferguson, p. 381.

[43] Ferguson, p. 381.

[44] Ferguson, p. 381.

[45] Ferguson, p. 382.

[46] Ferguson, p. 382.

[47] Ferguson, p. 409.

[48] Ferguson, p. 383.

[49] Takahashi Korekiyo, The Rothschilds and the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-06, pp. 20-21 cit. Gerry Docherty and Jim Macgregor, Hidden History: The Secret Origins of the First World War (Edinburgh & London: Mainstream Publishing, 2013), p. 93.

[50] Macgregor and Docherty, Prolonging the Agony, p. 442.

[51] Ferguson, p. 449.

[52] https://winteroak.org.uk/2022/10/14/a-crime-against-humanity-the-great-reset-of-1914-1918/

[53] Antony C. Sutton, Wall Street and the Bolshevik Revolution (Surrey: Clairview Books, 2016) (1974), p. 93.

[54] Sutton, p. 90.

[55] Macgregor and Docherty, Prolonging the Agony, p. 474.

[56] Macgregor and Docherty, Prolonging the Agony, p. 474.

[57] Quigley, Tragedy and Hope, p. 59.

[58] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russia

[59]

[60] https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_First40Years_Book_2010.pdf#page=124

[61] https://forumspb.com/en/news/news/russian-president-vladimir-putin-meets-with-world-economic-forum-chairman-klaus-schwab/

[62]

https://www.weforum.org/press/2021/10/russia-joins-centre-for-the-fourth-industrial-revolution-network

[63]

https://tadviser.com/index.php/Article:Smart_city:_development_in_Russia

[64] https://www.webuildvalue.com/en/megatrends/moscow-smart-city.html

[65] https://journals.aserspublishing.eu/jemt/article/view/1875

[66] https://www.reuters.com/markets/currencies/russia-start-piloting-digital-rouble-august-interfax-2023-07-11/

[67]

[68] Quigley, Tragedy and Hope, p. 71.

[69] Quigley, Tragedy and Hope, pp. 98-99.

[70] Carroll Quigley, The Anglo-American Establishment: From Rhodes to Cliveden (Dauphin Publications Inc, 2013), p.206.

[71] Christopher Hill, The Century of Revolution 1603-1714 (London: Sphere,1969), p. 42.

[72] Hill, p. 188.

[73] A.L. Morton, A People’s History of England (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1995), p. 174.

[74] Morton, p. 175.

[75] Morton, p. 261.

[76] Sri Aurobindo, Bande Mataram, The Complete Works of Sri Aurobdino (Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 2002), Vol 6-7, p. 271.

[77] Ferguson, p. 65.

[78] Ferguson, pp. 68-69.

[79] Ferguson, p. 69.

[80] Quigley, Tragedy and Hope, p. 84.

[81] Ferguson, p. 297.

[82] Ferguson, p. 301.

[83] Ferguson, p. 331.

[84] Ferguson, p. 332.

[85] Ferguson, p. 325.

[86] Docherty and Macgregor, Hidden History, p. 25.

[87] Ferguson, p. 332.

[88] Ferguson, p. 332.

[89] https://time.com/6248790/india-population-data-china/

[90] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/India

[91] https://www.narendramodi.in/worldeconomicforum_home

[92] https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/pm-narendra-modi-world-economic-forum-wef-davos-agenda-full-speech-1901161-2022-01-17

[93]

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/india/india-has-the-ability-to-lead-the-fourth-industrial-revolution-pm-modi/articleshow/94700634.cms

[94]

https://www.weforum.org/centre-for-the-fourth-industrial-revolution-india/about

[95] https://smartcities.gov.in/about-the-mission

[96] https://smartcities.gov.in/partners

[97] https://winteroak.org.uk/2022/04/15/charles-empire-the-royal-reset-riddle/

[98]

https://winteroak.org.uk/2021/01/11/shapers-of-slavery-the-empire/#6

[99]

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/03/impact-investors-india-new-research/

[100]

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/11/india-rolls-first-f-its-digital-rupee-currency/

[101]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Century_of_humiliation

[102] Quigley, Tragedy and Hope, p. 112.

[103] Quigley, Tragedy and Hope, p. 113.

[104] Quigley, Tragedy and Hope, p. 114.

[105] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opium_Wars

[106] Ferguson, p. 68.

[107] Ferguson, pp. 68-69.

[108] ‘The Modern Croesus’, The Period, July 5, 1870, see Ferguson. p. 159.

[109] Ferguson. p. 294.

[110] Ferguson, p. 383.

[111] Ferguson, p. 385.

[112] Ferguson, p. 385

[113] Ferguson, pp. 385-86.

[114] Ferguson, p. 387.

[115] Quigley, Tragedy and Hope, p. 641.

[116] Ferguson, p. 386-87.

[117] Ferguson, p. 387.

[118] Ferguson, p. 388.

[119] Ferguson, p. 388.

[120] Ferguson, p. 388.

[121] Quigley, Tragedy and Hope, p. 735.

[122]

https://www.rothschildandco.com/en/countries/greater-china/

[123]

https://www.foxnews.com/world/world-economic-forum-chair-klaus-schwab-declares-chinese-state-tv-china-model-many-nations

[124]

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/06/amnc23-premier-li-qiangs-opening-remarks-at-the-14th-annual-meeting-of-the-new-champions/

[125] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/China

[126] https://www.weforum.org/about/history/

[127]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_economic_reform

[128]

https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/102214/why-china-worlds-factory.asp

[129] https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201907/11/WS5d26cb19a3105895c2e7cee3.html

[130] https://www.weforum.org/centre-for-the-fourth-industrial-revolution-china

[131]

https://news.trust.org/item/20200624080235-95zxs

[132]

https://chinadevelopmentbrief.org/reports/impact-investing-in-china-challenges-and-opportunities/

[133]

https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3096090/what-chinas-social-credit-system-and-why-it-controversial

[134]

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/09/china-digital-yuan-app-ecny/

[135] Docherty and Macgregor, Hidden History, p. 31.

[136] Ferguson, p. 357.

[137] Ferguson, p. 357.

[138] Ferguson, p. 358.

[139] Ferguson, p. 358.

[140] Ferguson, p. 358.

[141] Ferguson, p. 352.

[142] Ferguson, p. 353.

[143] Ferguson, p. 359.

[144] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matabeleland

[145] Ferguson, p. 413.

[146] Ferguson, p. 361.

[147] Ferguson, p. 366.

[148] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_South_Africa_Company

[149] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Africa#Economy

[150]

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/09/world-economic-forum-africa-2019-ramaphosa-gender-violence-youth/

[151] https://www.gov.za/speeches/president-cyril-ramaphosa-wef-global-press-conference-23-jan-2019-0000

[152] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02589346.2019.1696003

[153]

https://businesstech.co.za/news/technology/477240/3-smart-cities-planned-for-south-africa/

[154]

https://techfinancials.co.za/2021/05/27/south-african-smart-cities-a-glimpse-of-a-connected-future/

[155] https://africaimpactsummit.org/

[156] http://www.impactinvestingsa.co.za/

[157] https://gsgii.org/

[158] https://winteroak.org.uk/2021/01/27/ronald-cohen-impact-capitalism-and-the-great-reset/

[159] https://mg.co.za/business/2021-05-25-south-africa-joins-digital-currency-race/

[160] https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/657487/reserve-bank-testing-digital-rand-in-south-africa/

[161] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jim_O%27Neill,_Baron_O%27Neill_of_Gatley

[162] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/authors/jim-oneill/

[163] https://www.bruegel.org/bruegel-european-think-tank-specialises-economics

[164] https://www.gov.uk/government/people/jim-oneill

[164] https://www.gov.uk/government/ministers/commercial-secretary-to-the-treasury

[165] https://www.chathamhouse.org/about-us/our-people/jim-oneill-0

[166] https://winteroakpress.files.wordpress.com/2022/12/enemiesofthepeople.pdf

[167] Quigley, The Anglo-American Establishment, p. 198.

[168]

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2021/06/jim-oneill-revisits-brics-emerging-markets.htm